In 2014, author Saul Austerlitz wrote a screedy New York Times op-ed against a strain of music writing that gets genuinely excited about glossy radio hits: poptimism. Critics in ivory towers, he argued, believe they’re oh so radical for placing Taylor Swift on the same plane as less obviously commercial, more artistically “serious” musicians. The irony is that so much of the world adores Swift – so how subversive can it be to expound upon the luminously lush leitmotifs in “Blank Space” (2014)?

More than a decade later, other forums for cultural criticism have tightly embraced mass culture, and the art responds in turn. It’s creativity as violent capitalist samsara, where everything enters into and is expelled by the body of market forces. If Pop used to be specific to individual artists (or at least distinct scenes) whose creativity radiated outward to a wide audience, today, no art, music, or fashion exists separately from an existing web of content that surrounds it. Every pop song is a mood board.

In this climate, two solo shows at the Salzburger Kunstverein refuse passive consumption of what’s popular. If poptimism asked us to take glossy surfaces seriously, these artists suggest we take seriously how we perceive the gloss. Esben Weile Kjær’s (*1992) “thousands of small explosions at the same time” plops dark-mode Disney sculptures atop bespoke wall-to-wall carpeting, constructing a nightmarish playroom that alternates neon and greyscale. Meanwhile, in the museum’s smaller studio space, “School of Seeing” consists of the late Palestinian artist Laila Shawa’s (1940–2022) graphic, frankly political art, including screenprints, painting, collage, and sculpture.

View of “thousands of small explosions at the same time,” Salzburger Kunstverein, 2025. Photo: kunst-dokumentation

View of “School of Seeing,” Salzburger Kunstverein, 2025. Photo: kunst-dokumentation

Despite the gulfs between their ages and contexts – Weile Kjær is thirty-three years old and from Denmark; Shawa, born in Gaza, was an eight-year-old during the Nakba – the artists share a visual language of repetition and excess. From color (bright, often garish), to material (slick, sticky, flat), to an urgency of bodily movement, the shows work remarkably well together. It’s their order of meaning that takes more meditation to parse.

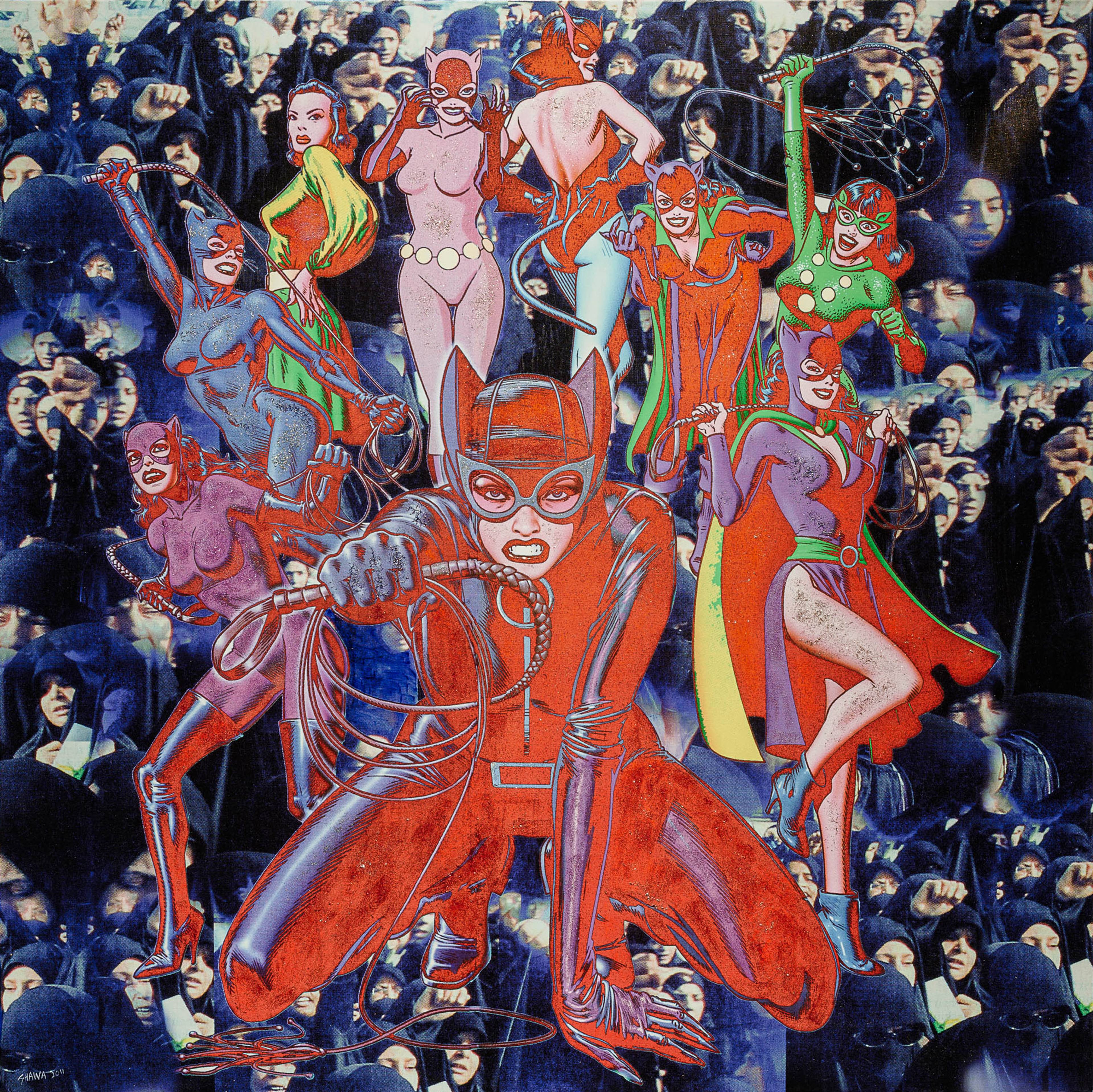

There was once a time when capital-P Pop art was critical of the commodity, before it became commodified itself. Tall, blonde, and charismatic, Weile Kjær and his increasingly in-demand Copenhagen studio are a Scandi-fied whiff of Andy Warhol and his Factory. Shawa often gets slapped with the label “Islamo-Pop,” a limiting framework, though she does feel, on a formal level, like an Arab answer to Warhol. Where he iconized Western media – celebrities, or supermarket items advertised within said media – Shawa photographically documented her homeland in a newspaperish grammar we immediately read as “Middle Eastern”: images of veiled women, of dead children, of suicide bombers – but multiplied, colorized, and scrawled over. No image is presented without Shawa’s markups, complicating how we see the photo of the small brown boy now splashed with blood-red and the faint outline of a bullseye on his forehead. To use a musicology term, she interpolates the original referent.

Ideas about the Arab world are constructed for the western voyeur out of political cartoons and censored erasures, mediated from the top down. Popular in particular is the iconography of Palestine, which is certainly not universally endorsed, but which reverberates across geography and time, despite the fact that the flag alone is routinely banned and that 189 Palestinian journalists have been killed in Gaza since 7 October 2023. We circulate the images of Gazans dying, and that Gazans died for, between images of comparative opulence – our own happy, healthy babies; our right to travel; our plodding along, alive. Weile Kjær’s carpet comprising two hundred photographic squares, a new work that gives his show its name, immerses us in the dissonance familiar to anyone with an Instagram account. Perhaps if we sit on the line bifurcating the kitten and the atom bomb, the irony will click.

If Pop used to be specific to individual artists whose creativity radiated outward to a wide audience, today, no art, music, or fashion exists separately from an existing web of content that surrounds it. Every pop song is a mood board.

I mean, I doubt it will. I think we’re too in it. We’re going to go back on our phones to repeat the motions. What we see there depends on our unique content buckets, where we interpret the kittens and the bombs the way people like us are supposed to. Weile Kjær makes analog experiences to highlight this weirdness of our digital lives: a space to lay down inside these “posts”; stained-glass works with the scaled-up dimensions of an iPhone that depict stills from previous live performances. “In my art practice, pop culture becomes a tool to capture the present and enhance it in order to see it for what it is,” he said in a 2021 interview. What it is: too much information.

Pop-cultural language also gives Shawa a springboard to address what we so often turn away from. But she was working before the lifestyle machine was fully operational. In the center of the studio stand two sculptures from her “Disposable Bodies” series (2011–13): mannequin torsos dolled up in tacky exotic-dancer garb – peacock feathers and a fake diamond necklace that reads SEX – and adorned with Semtex explosives and combat belts, the necessaries for executing a suicide bombing. A response to the story of a woman who failed to detonate at the Gaza border, “Disposable Bodies” is a relic from a time when news stayed with us longer than one scroll, when it was possible we’d all seen the same story, when we had a song of the summer.

Left: Laila Shawa, Disposable Bodies No. 5 (Paradise Now), 2012; right: Laila Shawa, Disposable Bodies No. 1 (Pride, Freedom, Land, Hope), 2011. Installation view, Salzburger Kunstverein, 2025

Esben Weile Kjær, Honeytrap, 2025, mannequins, costumes from the archives of the Salzburg Festival. Courtesy of the artist

Weile Kjær uses mannequins, too – they’re a low-lift reminder that “women be shopping” while the world is burning. Three figures from a sports equipment store wear rococo tassels and lace borrowed from the Salzburg Festival’s costume archive. Crystal-encrusted rodents scamper between them, the same size as the biggest rats in Copenhagen’s King’s Garden. Something something opulence? Something something elitism? It’s not always clear exactly what the artist wants to say about the signs and symbols of power that he steals and makes absurd. (More legible are his exhilarating live performances, where dancers mime a frenzied uprising as if the churn of optimization combusted once and for all.) But it’s captivating and stylish art, precisely because it looks really good while being left of center. Politics are rarely freaky in the way that Weile Kjær’s Spider (2024) is: a golden Tinky-Winky arachnid with legs as long as me, ready to crawl into the homes of the evangelical Christians who got him booted from The Teletubbies (1997–2001) for carrying a women’s purse.

In a room otherwise given over to Weile Kjær, seven Shawa pieces line one wall: small vessels embellished with rhinestones, beads, and plastic butterflies. “They’re giving Miuccia [Prada],” the Danish artist tells me. Shaped like perfume bottles, but also hand grenades, Shawa meant for them to scan as breast pumps. During treatment for mammarian cancer in 1990, she watched on TV as the US bombed Baghdad, saying of the experience, “The body woman and the body land amalgamate; the invasion of one is equated with the invasion of the other and the implicit fact that both leave scars.” Invited by the curators to browse Shawa’s archive, Weile Kjær chose to display the Breast Bombs in infinitely mirrored cases, recreating a department store’s fine jewelry displays. In his remix, they become a commentary on the repackaging of counterculture as consumer culture, turned around the lifestyle cycle of creation, consumption, and curation.

Esben Weile Kjær, Spider, 2024, bronze, approx. ⌀ 200 x 130 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Andersen’s, Copenhagen

Laila Shawa, Breast Bomb, 2017, beads, rhinestones, and various mixed media plastics, butterflies, 12 x

8 cm. Courtesy: the Laila Shawa Estate

Austerlitz’s most generous view of poptimism is that it wants “to privilege the deliriously artificial over the artificially genuine.” Weile Kjær uses the former to sneak in critiques of the latter; smile too long, and a grimace begins to emerge. Shawa, by contrast, is deliriously genuine. Her work lacks polish; there’s a tinge of art-school splatter, visible seams, and elementary literalism (see: “School of Seeing”). She is not a poptimist so much as a punk. When images of war become tradeable commodities in the press and on social media, how subversive can it be to replay them without a little graffiti-like intervention, however unflattering? What is high production value in the context of mass death?

Last summer, the model Bella Hadid stepped out at the Cannes Film Festival in a summer dress made from a keffiyeh, a cloth shawl worn as a symbol of Palestinian resistance since the 1930s. Hadid’s father is Palestinian, and the supermodel has openly condemned Israel’s genocide in Gaza. This summer, Chinese fast-fashion retailer SHEIN debuted a dupe of the dress that replaces the keffiyeh’s checkered pattern with tepid, girlie gingham. Such appropriation isn’t even exemplary of “cool capitalism” and the absorption of rebellion into something marketable; it’s straight to the erasure stage. There is no place for optimism in a defanged pop culture. There is no place for unexamined pop inside a murder machine.

___

This text was written during a month-long Writer-in-Residence program at the Salzburger Kunstverein, which was awarded in partnership with Spike. Read Annalise June Kamegawa on Mikołaj Sobczak here; a text from Gabrielle Schwarz is forthcoming later this year.

Esben Weile Kjær

“thousands of small explosions at the same time”

&

Laila Shawa

“School of Seeing”

Salzburger Kunstverein

26 Jul – 14 Sep 2025